The unprecedented state of preservation of a fossil from Southern Italy sheds light on Neanderthal facial morphology and the purported adaptations to cold climate

A team comprising researchers from Italy (University of Perugia, University of Pisa, and Sapienza University of Rome) and Spain (IPHES-CERCA – Catalan Institute of Human Paleoecology and Social Evolution, Rovira i Virgili University, Tarragona) has studi

Neanderthals are one of the most fascinating topics in the study of human evolution, as it is their unique facial morphology, characterized by a large nasal opening and a protruding midface (named by scholars ‘midfacial prognathism’). The Neanderthal nose, in particular, has been the focus of enduring debates, as it has a general structure that conflicts with what is expected in human populations adapted to cold climate. Yet, Neanderthal body characteristics and proportions reflect the adaptation to the harsh climatic conditions of Europe during the last phases of the Pleistocene, when the species lived.

The “paradox” of a large nasal opening characterized the species until its evolutionary demise: the extinction occurred around 40,000 years ago. Some scholars have explained this by identifying possible adaptations in the inner structures of the nose, unique to Neanderthals (autapomorphies), based on examining very fragmentary remains. The inner nose, in fact, is never preserved in the paleoanthropological fossil record, and is rarely preserved in archeological collections due to the fragility of its bony components. For this reason, such features represented the subject of a longstanding debate in the paleoanthropological community.

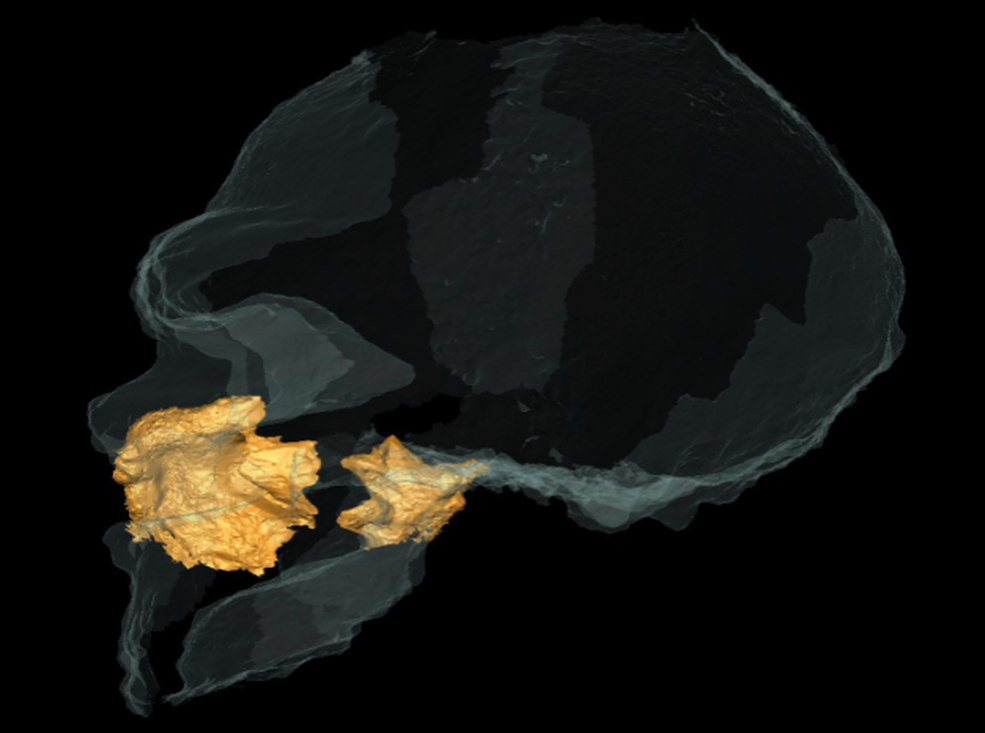

The new article by Dr. Costantino Buzi and colleagues, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), presents the unprecedented preservation of the inner nasal structures in the Neanderthal fossil skeleton from Altamura (Southern Italy). The skeleton, discovered in 1993, has been the subject of a series of in-depth studies only in the last decade. The specimen is between 130,000 and 172,000 years old, and the study was conducted by using endoscopic technology directly in the karstic system, where it is still preserved.

Professor Giorgio Manzi, from Sapienza University of Rome, one of the authors of the new article, highlights the importance of the specimen for the study of Neanderthal evolution and paleoanthropology at large: “The peculiar place and condition of deposition of the Altamura Neanderthal make it potentially the most complete human fossil skeleton ever discovered. Notwithstanding its elusive nature, due to the fact of being still ‘trapped’ in a very complex karstic system, it continues providing us with unprecedented information, also thanks to the innovative technologies used for its study”.

The specimen allowed the scientists to examine the internal morphology of a Neanderthal nasal cavity for the first time, ruling out the existence of adaptations of the inner nose unique to Neanderthals. “As pointed out by several authors in the past – explains Dr. Antonio Profico of the University of Pisa, who co-authored the paper – these traits were defined as diagnostic without clear fossil evidence. Altamura finally provided the evidence of their absence: even without these adaptations, the Neanderthal nose had an efficient model to fulfill the high energetic demands of the species”.

Professor Carlos Lorenzo of the IPHES-CERCA and Rovira i Virgili University of Tarragona concurs: “Once we take into account bioenergetics, the ‘paradox’ of the large nasal opening in Neanderthal is no longer a paradox. It is what we could expect from a cold-adapted species with and archaic cranial morphology. The nasal morphology that we can already see in the early Neanderthal from Altamura, even if different from that of modern humans, may have been the perfect morphological solution for the conditioning of the air in a massive body”.

Another finding is that the peculiar Neanderthal facial morphology – the midfacial prognathism – was most likely not shaped by upper respiratory function and should be traced back to other, likely cascading, evolutionary factors.

Dr Costantino Buzi, the leading author, now at the University of Perugia and research associate of IPHES-CERCA of Tarragona (where part of the study was carried out), concludes: “ What we can gather by looking at the nasal cavity of Altamura is that it “follows” the midfacial prognathism only in its anterior part, without substantial changes in its functional portion. We can conclude that the nose is not the primary driver of midfacial prognathism, even though it is influenced by it. Other adapting pressures and morphological constraints operated on the Neanderthal face, resulting in a model alternative to ours, yet perfectly functional for the harsh climate of the European Late Pleistocene”.

In addition, thanks to the endoscopic technology used, the authors could create a 3D model of the Neanderthal nose, which will provide a basis for future studies aimed at modelling and assessing the respiratory performance of this fossil species.

Reference

Buzi, C., Profico, A., Lorenzo, C., & Manzi, G. (2025). The first preserved nasal cavity in the human fossil record: The Neanderthal from Altamura. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 122(48). doi:10.1073/pnas.2426309122