Eating carrion may have made us human: The importance of scavenging in our evolution

A study involving IPHES-CERCA redefines the role of scavenging in human evolution, highlighting its importance as an efficient subsistence strategy complementary to hunting and gathering

A team of researchers from IPHES-CERCA has participated in a study led by the National Research Center on Human Evolution (CENIEH) that rethinks the role of carrion consumption in the history of our species. The paper, published in the journal Journal of Human Evolution, reviews this practice from the earliest hominins to the present and argues that scavenging was a fundamental and recurrent strategy throughout our evolution.

The research involved Dr. Jordi Rosell, professor at the Universitat Rovira i Virgili and researcher at IPHES-CERCA, and Dr. Maite Arilla, also a researcher at IPHES-CERCA, together with specialists from CENIEH, IREC-CSIC, IPE-CSIC, Universidad Miguel Hernández, and the universities of Alicante, Granada, and Málaga.

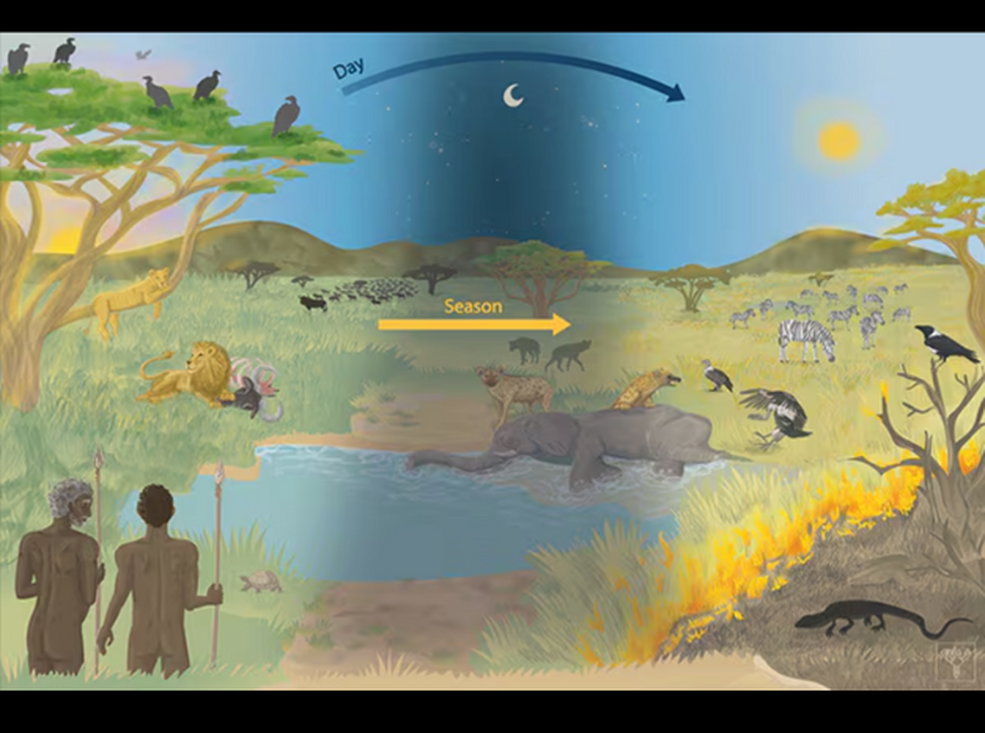

According to the authors, scavenging offered early humans major advantages: it allowed them to obtain food with far less effort than hunting and was especially valuable during periods of famine when other resources were scarce. Recent ecological research also shows that carrion is more predictable and abundant than previously thought, and that scavenger animals develop behaviors that reduce the risk of contracting diseases.

The researchers note that humans are anatomically, physiologically, and technologically adapted to be efficient scavengers. “The acidic pH of the human stomach may act as a defense against pathogens and toxins, and the risk of infection decreased considerably when we began to use fire for cooking. Moreover, our ability to travel long distances with low energy expenditure was key to finding food opportunities,” they explain.

Language and stone tools —even the simplest ones— facilitated collective organization to locate carcasses and gain access to meat, fat, and bone marrow. This combination of factors made scavenging a highly efficient activity, complementary to hunting and plant gathering.

In the 1960s, the discovery in Africa of the earliest evidence that ancient hominins ate meat sparked an intense debate: did they hunt these animals, or did they simply exploit the carcasses they found? For decades, scavenging was considered a “primitive” stage that humans had left behind once they learned to hunt. However, current studies have completely overturned this view: all carnivorous species consume carrion to some extent, and many modern hunter-gatherer groups continue to practice scavenging as part of their subsistence behavior.

The authors conclude that scavenging was not merely a transitional stage but a fundamental and recurrent strategy throughout human evolution, complementary to hunting and plant gathering. Ultimately, eating carrion (far from being a marginal behavior) was key to making us human.

Bibliographic reference:

Mateos, A., Moleón, M., Palmqvist, P., Rosell, J., Sebastián-González, E., Margalida, A., Sánchez-Zapata, J. A., Arilla, M., Rodríguez, J. (2025). Revisiting hominin scavenging through the lens of Optimal Foraging Theory. Journal of Human Evolution. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2025.103762